Image credit or source. First image. Second image. Third image: Alexey Pismenny.

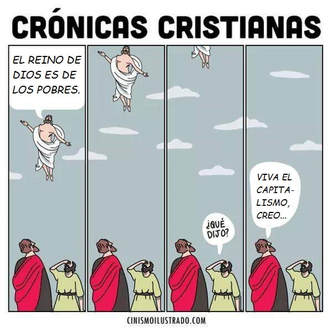

Apparently this cartoon is translated:

Frame 1: “The kingdom of God belongs to the poor.”

Frame 3: “What did he say?”

Frame 4: “I think he said, ‘Long live capitalism.’”

Apparently this cartoon is translated:

Frame 1: “The kingdom of God belongs to the poor.”

Frame 3: “What did he say?”

Frame 4: “I think he said, ‘Long live capitalism.’”

Acts 1:1-11

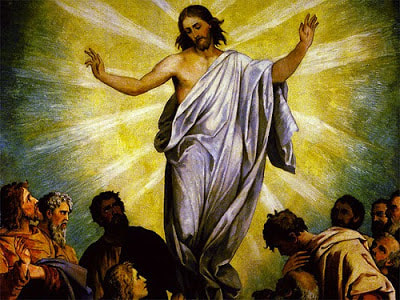

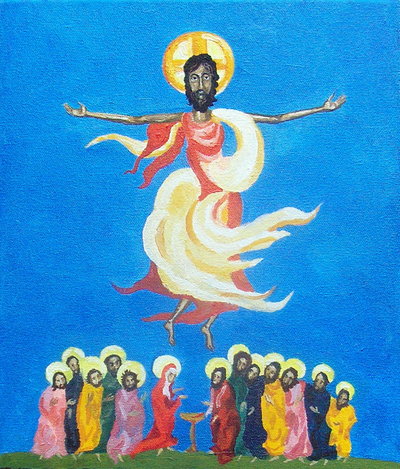

What draws me to these particular Ascension art works is that they don’t emphasise worship and awe. (Though I’m not against worship and awe!)

They do convey a sense of a group of people, Jesus’ disciples, who even as they stand there watching him remove, disappear, become physically absent from the world, have certain cogs turning in their minds: “Heavens! Jesus is going?! Jesus is gone?! So... it’s just us now?! Her, and him, and me, and that really annoying hot-head who talks and acts without thinking first? That’s... unexpected. That’s... risky. That’s... terrifying. What does this mean?! Oh. Dear.”

Jesus is leaving us?!

Jesus is leaving us?!

It is astonishing isn’t it?

Not just the miraculous ascent, the angelic presence, the lift off and removal of a beloved teacher... but the sudden stark focus on the collection of mere humans, left behind, somewhat stunned.

(But whatever I say about absence and loss and receiving responsibility, you need to remember: the Spirit of God is upon us. It’s just that we’ll get to that part of the story next Sunday with Pentecost!)

We heard:

So when they had come together, they asked him, ‘Lord, is this the time when you will restore the kingdom to Israel?’ He replied, ‘It is not for you to know the times or periods that the Father has set by his own authority. But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, in Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth.” When he had said this, as they were watching, he was lifted up, and a cloud took him out of their sight. (1:6-9)

The prophet Elijah was taken up to heaven in a fiery chariot (2 Kings 2:11), Enoch (the great grandfather of Noah) was taken in whirlwinds to the very end of the heaven (but you can’t read about in your bible – you have to go the non canonical Book of Enoch), and Moses, according to Philo, the ancient Jewish philosopher, ascended to God while proclaiming God’s word. In the stories of Exodus, a cloud accompanies God’s people as a symbol of God’s faithful presence among them. And then a cloud endorses Jesus at his transfiguration (Luke 9:34).

While he was going and they were gazing up towards heaven, suddenly two men in white robes stood by them. They said, “Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking up towards heaven?” This Jesus, who has been taken up from you into heaven, will come in the same way as you saw him go into heaven.” (Acts 1:10-11)

These two could be the angels from the empty tomb, or they could be Moses and Elijah – who were present at the transfiguration, and as I said, also ascended.

In these few verses are reminders of Jewish heritage and expectation, and reminders of what it has meant to have Jesus as a flesh and blood companion.

But the story moves into alarming new territory too. And perhaps what is dawning on the disciples, depicted in the three ascension scenes, is what Teresa of Avila (1515–1582) expresses so well:

Christ has no body but yours,

No hands, no feet on earth but yours,

Yours are the eyes with which he looks

Compassion on this world,

Yours are the feet with which he walks to do good,

Yours are the hands, with which he blesses all the world.

Yours are the hands, yours are the feet,

Yours are the eyes, you are his body.

Christ has no body now but yours,

No hands, no feet on earth but yours,

Yours are the eyes with which he looks

compassion on this world.

Christ has no body now on earth but yours.

If indeed this reality is dawning on them, they’re probably wishing they had asked some more specific questions about being the body of Christ for the world. To think that at the Last Supper they squandered valuable time discussing who would be greatest! To think that after Jesus’ resurrection they feed him fish instead of asking:

How will we know what you want us to do, how you want us to carry on on your behalf? How should we organise ourselves? Should someone be in charge? How should we identify that person? What are your thoughts on a Pope? Tele-evangelists? What should we do when some of us believe God wants us to buy a house and fight gentrification in our area, and others are unconvinced? What should we do if the law around marriage changes, and some of us believe it is good, and others believe it is bad?

It’s true Jesus gave guidance for his physical absence. Think of the wonderful farewell sayings in John’s gospel. But if the disciples had understood what they were in for, they might have asked more follow up questions.

Christ has no body now on earth but yours.

Teresa’s words can be read individually; to strive in our personal individual lives to do good works and be Christ-like. But it can also be read collectively, and there is no doubt that in physical removal, Christ gives the task of continuing his mission and ministry, his message, his very self, to the collective of slightly stunned, slightly disturbed disciples, including you and me, us.

Given that we are to be the body of Christ, it makes sense that we also have to discern the mind of Christ. You might have heard this phrase thrown around a bit, especially by Baptists who don’t have top down structures and bishops to tell us what to do – we have congregations who must discern the mind of Christ and act accordingly. Is it code for doing whatever we like, spouting our own agenda and hoping for the best?

With the fabulous theology that comes to us with Ascension and Pentecost, and with the Assembly Council “listening hui” and invitation to discern what kind of leadership our movement needs, I want to open up for our serious consideration the question of discerning the mind of Christ in order to be the body of Christ – how does an ordinary congregation go about this lofty business?

I’m drawn to the Quaker ideas of discernment. A group sitting in attentive silence, waiting on the guidance of the Spirit, speaking only if they know God is prompting them to, unity reached without any argy-bargy, perhaps hardly any talking.

But I recognise this is not how Baptists have developed our discernment practice. (I know we don’t all identify as “Baptist” – it’s just that we do have Baptist principles in the set up of our church and church governance, so Baptist discernment and decision making is relevant.)

Martin Sutherland in his booklet Radical Disciples: exploring Baptist ideas (34-35)

“Christianity is not about a series of disconnected individuals, each interested only in their own hotline to God. The covenanted community [that’s members, or more broadly, people who have agreed to be a church together] is itself an expression of the kingdom of God and individual faith is to be exercised among others.”

“It is fundamental to the Baptist view of congregational church that the Spirit is uniquely active in the ‘coming together’ of believers. Baptists takes very seriously Jesus’ words in Matthew 18:15-20, when he anchored the authority of the community in his own presence ‘wherever two or three are gathered in my name’. Gathering in Jesus’ name is the key church event. It is in this coming together that the body is physically made ‘one’ and when it hears the voice of God most authentically and reliably.”

“The congregational meeting is not a space for arguing, neither is it a place for democracy as such. But then, neither is it a mass rabble that is to be manipulated or harassed by leaders or factions. It is the gathering of disciples who, together, are seeking the mind of the Spirit. In this process it is essential that all voices have an opportunity to be heard, because all are children of God and all have the Spirit in equal measure.”

Steve Holmes, in his chapter Knowing Together the Mind of Christ: congregational government and the church meeting suggests that we need an understanding of each and every person’s lack of competence. “...in the matter which is core of the church meeting, discerning the mind of Christ, everyone present is always utterly incompetent, unless and until Christ should graciously aid them by the Spirit.” (184) He also states that reflecting on Scripture together is essential to discerning together, and that “conversation, discussion, exchange of ideas, and even argument are a necessary part of the process.” (175-176)

Gathering.

Scripture, worship, prayer, conversation, robust conversation.

Hearing from everyone.

Knowing that no one is an expert on the mind of Christ – but that we find our way in the mix of each and every person who has committed to the body of Christ expressed in this particular collection of disciples.

And trusting that God’s Spirit is upon us.

Don't go away feeling overwhelmed by responsibility and inadequacy! Ideally you’ll be inspired about the gift of gathering and discerning, but if not inspired, perhaps you’ll have a fresh curiosity about what it means to look around this group who have gathered because of Jesus, believing together:

Christ has no body now on earth but yours.

(Lord's prayer)

What draws me to these particular Ascension art works is that they don’t emphasise worship and awe. (Though I’m not against worship and awe!)

They do convey a sense of a group of people, Jesus’ disciples, who even as they stand there watching him remove, disappear, become physically absent from the world, have certain cogs turning in their minds: “Heavens! Jesus is going?! Jesus is gone?! So... it’s just us now?! Her, and him, and me, and that really annoying hot-head who talks and acts without thinking first? That’s... unexpected. That’s... risky. That’s... terrifying. What does this mean?! Oh. Dear.”

Jesus is leaving us?!

Jesus is leaving us?!

It is astonishing isn’t it?

Not just the miraculous ascent, the angelic presence, the lift off and removal of a beloved teacher... but the sudden stark focus on the collection of mere humans, left behind, somewhat stunned.

(But whatever I say about absence and loss and receiving responsibility, you need to remember: the Spirit of God is upon us. It’s just that we’ll get to that part of the story next Sunday with Pentecost!)

We heard:

So when they had come together, they asked him, ‘Lord, is this the time when you will restore the kingdom to Israel?’ He replied, ‘It is not for you to know the times or periods that the Father has set by his own authority. But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, in Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth.” When he had said this, as they were watching, he was lifted up, and a cloud took him out of their sight. (1:6-9)

The prophet Elijah was taken up to heaven in a fiery chariot (2 Kings 2:11), Enoch (the great grandfather of Noah) was taken in whirlwinds to the very end of the heaven (but you can’t read about in your bible – you have to go the non canonical Book of Enoch), and Moses, according to Philo, the ancient Jewish philosopher, ascended to God while proclaiming God’s word. In the stories of Exodus, a cloud accompanies God’s people as a symbol of God’s faithful presence among them. And then a cloud endorses Jesus at his transfiguration (Luke 9:34).

While he was going and they were gazing up towards heaven, suddenly two men in white robes stood by them. They said, “Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking up towards heaven?” This Jesus, who has been taken up from you into heaven, will come in the same way as you saw him go into heaven.” (Acts 1:10-11)

These two could be the angels from the empty tomb, or they could be Moses and Elijah – who were present at the transfiguration, and as I said, also ascended.

In these few verses are reminders of Jewish heritage and expectation, and reminders of what it has meant to have Jesus as a flesh and blood companion.

But the story moves into alarming new territory too. And perhaps what is dawning on the disciples, depicted in the three ascension scenes, is what Teresa of Avila (1515–1582) expresses so well:

Christ has no body but yours,

No hands, no feet on earth but yours,

Yours are the eyes with which he looks

Compassion on this world,

Yours are the feet with which he walks to do good,

Yours are the hands, with which he blesses all the world.

Yours are the hands, yours are the feet,

Yours are the eyes, you are his body.

Christ has no body now but yours,

No hands, no feet on earth but yours,

Yours are the eyes with which he looks

compassion on this world.

Christ has no body now on earth but yours.

If indeed this reality is dawning on them, they’re probably wishing they had asked some more specific questions about being the body of Christ for the world. To think that at the Last Supper they squandered valuable time discussing who would be greatest! To think that after Jesus’ resurrection they feed him fish instead of asking:

How will we know what you want us to do, how you want us to carry on on your behalf? How should we organise ourselves? Should someone be in charge? How should we identify that person? What are your thoughts on a Pope? Tele-evangelists? What should we do when some of us believe God wants us to buy a house and fight gentrification in our area, and others are unconvinced? What should we do if the law around marriage changes, and some of us believe it is good, and others believe it is bad?

It’s true Jesus gave guidance for his physical absence. Think of the wonderful farewell sayings in John’s gospel. But if the disciples had understood what they were in for, they might have asked more follow up questions.

Christ has no body now on earth but yours.

Teresa’s words can be read individually; to strive in our personal individual lives to do good works and be Christ-like. But it can also be read collectively, and there is no doubt that in physical removal, Christ gives the task of continuing his mission and ministry, his message, his very self, to the collective of slightly stunned, slightly disturbed disciples, including you and me, us.

Given that we are to be the body of Christ, it makes sense that we also have to discern the mind of Christ. You might have heard this phrase thrown around a bit, especially by Baptists who don’t have top down structures and bishops to tell us what to do – we have congregations who must discern the mind of Christ and act accordingly. Is it code for doing whatever we like, spouting our own agenda and hoping for the best?

With the fabulous theology that comes to us with Ascension and Pentecost, and with the Assembly Council “listening hui” and invitation to discern what kind of leadership our movement needs, I want to open up for our serious consideration the question of discerning the mind of Christ in order to be the body of Christ – how does an ordinary congregation go about this lofty business?

I’m drawn to the Quaker ideas of discernment. A group sitting in attentive silence, waiting on the guidance of the Spirit, speaking only if they know God is prompting them to, unity reached without any argy-bargy, perhaps hardly any talking.

But I recognise this is not how Baptists have developed our discernment practice. (I know we don’t all identify as “Baptist” – it’s just that we do have Baptist principles in the set up of our church and church governance, so Baptist discernment and decision making is relevant.)

Martin Sutherland in his booklet Radical Disciples: exploring Baptist ideas (34-35)

“Christianity is not about a series of disconnected individuals, each interested only in their own hotline to God. The covenanted community [that’s members, or more broadly, people who have agreed to be a church together] is itself an expression of the kingdom of God and individual faith is to be exercised among others.”

“It is fundamental to the Baptist view of congregational church that the Spirit is uniquely active in the ‘coming together’ of believers. Baptists takes very seriously Jesus’ words in Matthew 18:15-20, when he anchored the authority of the community in his own presence ‘wherever two or three are gathered in my name’. Gathering in Jesus’ name is the key church event. It is in this coming together that the body is physically made ‘one’ and when it hears the voice of God most authentically and reliably.”

“The congregational meeting is not a space for arguing, neither is it a place for democracy as such. But then, neither is it a mass rabble that is to be manipulated or harassed by leaders or factions. It is the gathering of disciples who, together, are seeking the mind of the Spirit. In this process it is essential that all voices have an opportunity to be heard, because all are children of God and all have the Spirit in equal measure.”

Steve Holmes, in his chapter Knowing Together the Mind of Christ: congregational government and the church meeting suggests that we need an understanding of each and every person’s lack of competence. “...in the matter which is core of the church meeting, discerning the mind of Christ, everyone present is always utterly incompetent, unless and until Christ should graciously aid them by the Spirit.” (184) He also states that reflecting on Scripture together is essential to discerning together, and that “conversation, discussion, exchange of ideas, and even argument are a necessary part of the process.” (175-176)

Gathering.

Scripture, worship, prayer, conversation, robust conversation.

Hearing from everyone.

Knowing that no one is an expert on the mind of Christ – but that we find our way in the mix of each and every person who has committed to the body of Christ expressed in this particular collection of disciples.

And trusting that God’s Spirit is upon us.

Don't go away feeling overwhelmed by responsibility and inadequacy! Ideally you’ll be inspired about the gift of gathering and discerning, but if not inspired, perhaps you’ll have a fresh curiosity about what it means to look around this group who have gathered because of Jesus, believing together:

Christ has no body now on earth but yours.

(Lord's prayer)