(by Jody)

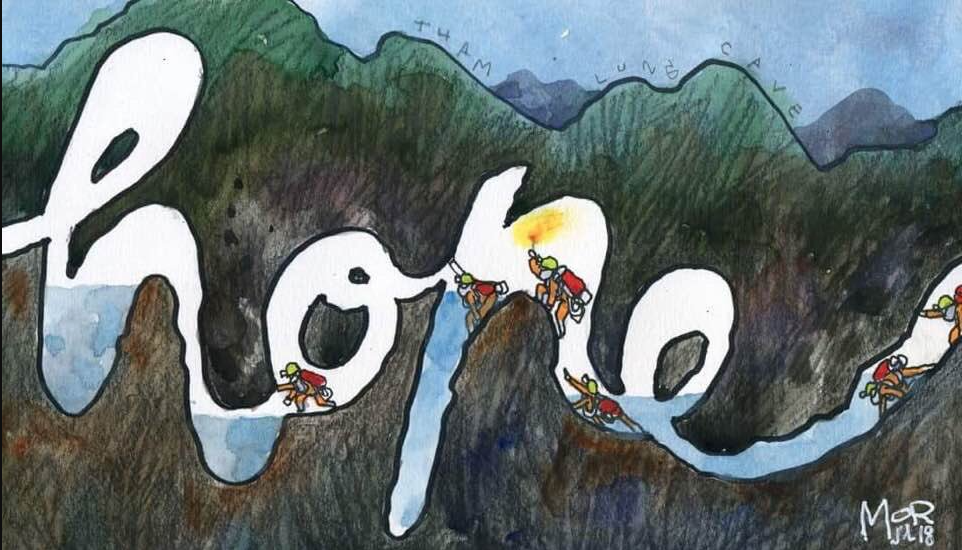

The inspiration for this sermon series came from this image, published in 2018. It was published partway through the recuse operation to get a junior football team and their assistant coach out of the cave they were trapped in Tham Luang, Thailand. And when I saw it, I thought, as preachers do: “there’s a sermon right there.”

I used this illustration with the Fusion group last week, and bless their youthful hearts, none of them remembered this event unfolding in real time like many of us older folk do. So in case you are quite young or somehow missed it:

A football team, boys aged 11 to 16, along with their 25 year old assistant coach, went for a fun little adventure into a local cave system. The caves were accessible to ordinary people, and the time of year they visited was outside of the seasonal flooding warning-against-entry dates.

While they were inside, heavy rain fell, and flooded part of the cave, including their exit point. The team was trapped on a ledge for 9 days before they were found by divers who had been searching for them. They remained trapped, but with support and some supplies, for another 6 to 8 days before they were all, incredibly, brought out safely.

Summarised in a paragraph it sounds quite simple, but details are harrowing. I read somewhere, but now can’t find the reference, that what was achieved in rescuing the boys and their coach compares to the first moon landing. I’m not sure how that can be calculated, especially since I can’t find the reference and might have made it up… but a whole lot of determination and resource and skill and wielding risk was in involved.

The rescue involved more than 10 000 people, including 100 divers from Thailand and around the world, representatives from 100 government agencies, 2 000 soldiers, assistance from at least 25 countries, including Ukraine and Russia. A billion litres of water was pumped from the caves, and it had to go somewhere. Two divers died, one at the time and one from blood poisoning over a year later.

What captivated me about this image was that the hope held involved absolute commitment and relentless action. People like me had hope, that the boys would be found and rescued, and I’d wake each day as the story unfolded, hoping for good news. But I didn’t have anything more to offer. For 10 000 others, the hope held was incredibly active: they gave their skill, courage, well-being, resources, livelihoods, reputations, lives. And ironically, I gather those most involved were not confident they could get all the boys out alive. It was easier to have hope and confidence from a distance than when you really understood what was going on. And yet they relentlessly worked in dark narrow spaces for hope.

It was great that Jeff flagged this story last week in relation to surrender, because my reflections on the story had only been on how much work goes into hope. But Jeff noted the surrender element: the boys and families put their lives into the hands of other people.

So while the resolute activity of this picture was what drew me to the hope series, because I imagined that it would be all about how hope and action are completely intertwined, it turned out that we wouldn’t get to that until week 3, since confidence in who God is, and surrendering of our own cherished outcomes, found their way to the foreground of hope.

But we are here now. Because hope and action definitely belong together. The pairing is formational, foundational, and transformational.

The bible reading is from the Book of James. In many ways it needs no comment, because it rings so true: that our treasured patterns of meaning and making sense – such as faith, and it’s not hard to stretch to hope with that – flourish in harmony with action, deeds.

James might have been written by the brother of Jesus, in which case; a first-hand account of the outworking of Jesus’ life and teaching soon after the fact, or James might have been written by an unknown source at an unknown time, in which case; we have no idea who wrote it, when, or what motivated the writing. James is wisdom literature, and makes broad points about careful Christian living, rather than addressing specific issues encountered in one church community.

Apparently Martin Luther believed that because the Book of James did not match precisely what Paul said in NT letters, especially on the subject of faith and works, it could not be as important as Paul’s writing. So James hasn’t had easy access in Protestant churches. But we know the truth of it.

James warns against learning all the right words but never doing anything, calls God-talk without God-acts “outrageous nonsense,” and imagines the two fitting together hand in glove.

The things we most believe in badger our whole selves to be involved, will never be satisfied with statements from our brains alone.

We know it. Not just with the cave rescue in 2018 but in human rights movements, safety laws, vaccine schedules, access and inclusion, single use plastic bag bans.

I guess the cave rescue had a timeline and set of characters we could wrap our heads and hearts around, many other crises don’t come to us so well contained or presented. We can’t help but think with awe and regret: imagine if the whole got behind every child in difficulty like we did with the boys in the cave. Imagine.

Perhaps it’s all too obvious and tedious to state. Janice named the tension of hope the other week – clutching God, but feeling overwhelmed by all that needs doing, changing, tending to. Pam noted the simple value of planting a garden in the face of climate change. Rob talked about the wrestle between surrender and action. All of that, and more, is true.

The story of hope can only be told in long, lived form. In each of our lives, and in our human lives together.

In a Guardian write up of the new Tham Luang rescue movie, Thirteen Lives, Stuart Jeffries notes:

“Anyone hoping for a story in which heroic Brits and Aussies save the day while the locals cheer from the sidelines is in for a shock. Howard’s film meticulously shows that the rescue effort involved more than 10,000 people, mostly Thai, but with volunteers flying in from around the world to offer their skills.”

“We’ve seen this sort of thing happen before, in the tsunami in Japan, when humanity pulls together,” says Thirteen Lives’ co-producer Vorakorn Reutaivanichkul... “Ron’s a very humanistic director so he wanted to show how people from all cultures and walks of life worked together to make the rescue happen. We really didn’t want another white-saviour* narrative. Not just because we’ve seen it too many times in films, but because it isn’t what happened. The film is uplifting about what humans do in crisis, which is, I think, what we need in this modern world.”

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, a marine biologist, co-founder of the Urban Ocean Lab, and podcaster on “How to save a planet,” says (in an On Being interview):

I mean, the most depressing thing I can think of is to just watch the world burn and crumble before my eyes while I just wallow in self-pity on the couch. … So I don’t have any delusions that I can “save the planet,” but you’ve got to try to do your part. … I’ve always been focused on solutions. I have this extremely practical approach to most things — I’m like, OK, who’s doing what? What’s the plan? …let’s figure out what’s next. And so that is the vibe that I’ve tried to take into my work as it’s broadened from oceans to climate more generally, is we have most of the solutions we need at our fingertips, for all of these climate challenges, whether it’s agriculture or green building retrofits or bike lanes or composting or wind energy in the ocean or farming seaweed or whatever. We know how to do this stuff. We just have to do it. And so figuring out how we can welcome more people into this work, get people excited, help them find where they fit, is really where I’ve been focusing my yammering energies, these days.”

How can we welcome more people to the work of hope? It’s a question for a church to live by.

*Peter pointed out in Free-for-all that my use of this quote in the sermon sounded like I dismissing any saviour! Not in the case of Jesus, I promise! Just human grandstanding when cooperation could achieve more.

The inspiration for this sermon series came from this image, published in 2018. It was published partway through the recuse operation to get a junior football team and their assistant coach out of the cave they were trapped in Tham Luang, Thailand. And when I saw it, I thought, as preachers do: “there’s a sermon right there.”

I used this illustration with the Fusion group last week, and bless their youthful hearts, none of them remembered this event unfolding in real time like many of us older folk do. So in case you are quite young or somehow missed it:

A football team, boys aged 11 to 16, along with their 25 year old assistant coach, went for a fun little adventure into a local cave system. The caves were accessible to ordinary people, and the time of year they visited was outside of the seasonal flooding warning-against-entry dates.

While they were inside, heavy rain fell, and flooded part of the cave, including their exit point. The team was trapped on a ledge for 9 days before they were found by divers who had been searching for them. They remained trapped, but with support and some supplies, for another 6 to 8 days before they were all, incredibly, brought out safely.

Summarised in a paragraph it sounds quite simple, but details are harrowing. I read somewhere, but now can’t find the reference, that what was achieved in rescuing the boys and their coach compares to the first moon landing. I’m not sure how that can be calculated, especially since I can’t find the reference and might have made it up… but a whole lot of determination and resource and skill and wielding risk was in involved.

The rescue involved more than 10 000 people, including 100 divers from Thailand and around the world, representatives from 100 government agencies, 2 000 soldiers, assistance from at least 25 countries, including Ukraine and Russia. A billion litres of water was pumped from the caves, and it had to go somewhere. Two divers died, one at the time and one from blood poisoning over a year later.

What captivated me about this image was that the hope held involved absolute commitment and relentless action. People like me had hope, that the boys would be found and rescued, and I’d wake each day as the story unfolded, hoping for good news. But I didn’t have anything more to offer. For 10 000 others, the hope held was incredibly active: they gave their skill, courage, well-being, resources, livelihoods, reputations, lives. And ironically, I gather those most involved were not confident they could get all the boys out alive. It was easier to have hope and confidence from a distance than when you really understood what was going on. And yet they relentlessly worked in dark narrow spaces for hope.

It was great that Jeff flagged this story last week in relation to surrender, because my reflections on the story had only been on how much work goes into hope. But Jeff noted the surrender element: the boys and families put their lives into the hands of other people.

So while the resolute activity of this picture was what drew me to the hope series, because I imagined that it would be all about how hope and action are completely intertwined, it turned out that we wouldn’t get to that until week 3, since confidence in who God is, and surrendering of our own cherished outcomes, found their way to the foreground of hope.

But we are here now. Because hope and action definitely belong together. The pairing is formational, foundational, and transformational.

The bible reading is from the Book of James. In many ways it needs no comment, because it rings so true: that our treasured patterns of meaning and making sense – such as faith, and it’s not hard to stretch to hope with that – flourish in harmony with action, deeds.

James might have been written by the brother of Jesus, in which case; a first-hand account of the outworking of Jesus’ life and teaching soon after the fact, or James might have been written by an unknown source at an unknown time, in which case; we have no idea who wrote it, when, or what motivated the writing. James is wisdom literature, and makes broad points about careful Christian living, rather than addressing specific issues encountered in one church community.

Apparently Martin Luther believed that because the Book of James did not match precisely what Paul said in NT letters, especially on the subject of faith and works, it could not be as important as Paul’s writing. So James hasn’t had easy access in Protestant churches. But we know the truth of it.

James warns against learning all the right words but never doing anything, calls God-talk without God-acts “outrageous nonsense,” and imagines the two fitting together hand in glove.

The things we most believe in badger our whole selves to be involved, will never be satisfied with statements from our brains alone.

We know it. Not just with the cave rescue in 2018 but in human rights movements, safety laws, vaccine schedules, access and inclusion, single use plastic bag bans.

I guess the cave rescue had a timeline and set of characters we could wrap our heads and hearts around, many other crises don’t come to us so well contained or presented. We can’t help but think with awe and regret: imagine if the whole got behind every child in difficulty like we did with the boys in the cave. Imagine.

Perhaps it’s all too obvious and tedious to state. Janice named the tension of hope the other week – clutching God, but feeling overwhelmed by all that needs doing, changing, tending to. Pam noted the simple value of planting a garden in the face of climate change. Rob talked about the wrestle between surrender and action. All of that, and more, is true.

The story of hope can only be told in long, lived form. In each of our lives, and in our human lives together.

In a Guardian write up of the new Tham Luang rescue movie, Thirteen Lives, Stuart Jeffries notes:

“Anyone hoping for a story in which heroic Brits and Aussies save the day while the locals cheer from the sidelines is in for a shock. Howard’s film meticulously shows that the rescue effort involved more than 10,000 people, mostly Thai, but with volunteers flying in from around the world to offer their skills.”

“We’ve seen this sort of thing happen before, in the tsunami in Japan, when humanity pulls together,” says Thirteen Lives’ co-producer Vorakorn Reutaivanichkul... “Ron’s a very humanistic director so he wanted to show how people from all cultures and walks of life worked together to make the rescue happen. We really didn’t want another white-saviour* narrative. Not just because we’ve seen it too many times in films, but because it isn’t what happened. The film is uplifting about what humans do in crisis, which is, I think, what we need in this modern world.”

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, a marine biologist, co-founder of the Urban Ocean Lab, and podcaster on “How to save a planet,” says (in an On Being interview):

I mean, the most depressing thing I can think of is to just watch the world burn and crumble before my eyes while I just wallow in self-pity on the couch. … So I don’t have any delusions that I can “save the planet,” but you’ve got to try to do your part. … I’ve always been focused on solutions. I have this extremely practical approach to most things — I’m like, OK, who’s doing what? What’s the plan? …let’s figure out what’s next. And so that is the vibe that I’ve tried to take into my work as it’s broadened from oceans to climate more generally, is we have most of the solutions we need at our fingertips, for all of these climate challenges, whether it’s agriculture or green building retrofits or bike lanes or composting or wind energy in the ocean or farming seaweed or whatever. We know how to do this stuff. We just have to do it. And so figuring out how we can welcome more people into this work, get people excited, help them find where they fit, is really where I’ve been focusing my yammering energies, these days.”

How can we welcome more people to the work of hope? It’s a question for a church to live by.

*Peter pointed out in Free-for-all that my use of this quote in the sermon sounded like I dismissing any saviour! Not in the case of Jesus, I promise! Just human grandstanding when cooperation could achieve more.